Free as in "free speech"

How to fund your open-source development

Some thoughts and ideas about the future of open-source extension funding in a business world and how projects like TYPO3 can still be consistent with free software principles.

Estimated time to read: 10 minutes

Freedom

Free as in "free speech" not as in "free beer"

From the very beginning of the free software movement there were lots of discussions about the principles of free software. Especially when it comes to commercial use of free or open-source software, there are completely different conceptions of these principles and how they correlate to those of capital driven markets.

While there are the two terms "Free Software" and "Open-Source Software" determining two different ideological points of view, they both share one understanding of the code and the underlying licenses: Everybody should have the freedom to use or modify the code of that kind of software and share it with others as long as they stick to the rules of the given license.

Richard Stallman, one of the key figures of the free software movement, actually states it clearly and unmistakably:

Free software is software that respects your freedom and the social solidarity of your community.

So it's free as in freedom.

One of the major open-source licenses is the General Public License or GPL. It is the license of the TYPO3 project, which is our choice as an example for the different financial problems you have to tackle as a developer, seller or user of GPLed software.

Free software ≠ Freeware

Two major misconceptions about open-source software

Although the free software movement has been around for more than three decades, there still are several misconceptions about free software as Dave Kelly and Cody v. d. Mark pointed out in their 2012 article "Six misconceptions of Open-Source Software".

In this article we will focus on the financial aspects though, which are primarily caused by the ambiguous meaning of the English word "free", which most people mistook as "for free", bringing them to the conclusion that "Free software" was just a synonym for "Freeware", so they expected it to be available free of cost. In fact freeware does not even have to be open-source at all, since even proprietary software can legally be downloaded for free.

This is why we will use the term "Open-Source Software" here, which is less misleading but still pointing out the principle of the freely accessible source code of that software.

For years creators and sellers of open-source software had to fight against the stereotype of the freaky nerds, the nighthawks, spending their whole spare time hacking code for free while eating tons of pizza and drinking gallons of coffee.

Granted, coffee and pizza are not that far-fetched, but the rest is a cliché that is still around today and it makes it hard to explain, that even those freaky nerds might have to make a living somehow, and that it does not come for free at all.

So let's clarify the two major misconceptions.

First of all open-source software even though published under the terms of the General Public License is not necessarily available for free, because the GPL does not require it to be at all.

And second open-source software development and maintenance usually comes at a cost as well, since people creating that software are often highly skilled professionals who code for a living.

The good thing about GPLed open-source code though is that everybody can be a part of the developing community and people can make a living based on it even when they haven't got any kind of seed capital. Of course this means to assume the code they are working on has been shared already, as it has been done with the code of the TYPO3 project.

Money won't create success, the freedom to make it will.

Still creators and users of GPLed software are allowed to give it away for free whenever they like, which brings us into the catch-22 situation, that selling open-source software might be a successful business model, but it could easily be destroyed by the first fork being available for free.

Now the goal is to find a business model that can be both, sustainable and compatible to the principles of open-source, at the same time. So let's take a look at the options.

Donations

It is more blessed to give than to receive

Since the founder of the TYPO3 project, Kasper Skårhøj, is a personal Christian, the first steps he made into the world of open-source were based on some very Christian principles as well. While feeling obliged by his belief to give away the code for free, he happily received donations from the users in return. For quite some time you could send him one or more cigars from a small dedicated online shop, which was one of the few vice he admitted to have.

Today there are still quite some extensions in the TYPO3 extension repository that make use of several ways to collect donations from their users. You can implement a donation link into the TER configuration of your extension or you can put a link to Flattr, Paypal or the like into your documentation or the about section, that will be visible in the backend.

People even created some kind of nagware that reminds people from time to time, that it would be nice to donate for the extension, if it has been useful to them and that the message would go away as soon as they made a donation.

Speaking for myself I decided to do it as Kasper did and created an Amazon wish list for my vice, which is whisky, not cigars. But I think we can all agree, that donations are on the one hand a really nice way to show your appreciation for the work of others, but on the other hand the income you can make based on donations is far from making a living out of it. Of course this might work as soon as your extension is used by millions of people, but this is very seldom in the TYPO3 universe.

So the usual donations won't be a topic for upcoming articles about that subject. Let's see what else we've got.

Association

Two's company, three's a crowd, four or more is an association

Another option for the funding of an open-source project is a non-profit organisation that takes care of the financial and legal matters of that particular project. For the TYPO3 project this has been done more than a decade ago, when the TYPO3 association was founded in 2004.

While having an association with members and fees on the one hand is a good idea when it comes to legal issues, strategical planning and official representatives for the project, on the other hand it might be at least questionable as a credit instrument for extension development.

It involves a lot of bureaucracy, takes too much time to take instant decisions and leads to a lot of unnecessary disruption especially when it's about negotiating the budgets between the different applicants, since in most of the cases there is not enough budget to please everyone.

Daniel Hinderink gave a talk about the lessons learned at the TYPO3 conference last year that clearly pointed out some pitfalls induced by the structures of this association and the way they had been established. Still having the association as one option to finance TYPO3 extension development seems to be reasonable, so this will be a topic for the next article about the subject.

Crowdfunding

Many a little makes a mickle

In 2012 with the TYPO3 association having become the major funding source for the TYPO3 core and other teams as well as the NEOS project, which was still around then, we needed some other ways to finance extension development. This is when crowdfunding came into play, since it was a way to collect money for clearly defined goals from a clearly defined target group.

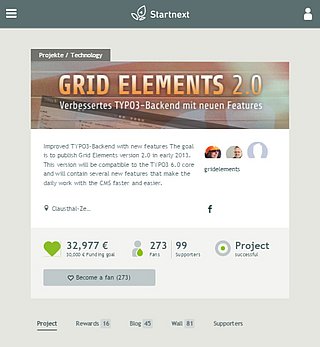

The Gridelements 2.0 refactoring was one of the first officially crowdfunded extension projects in the TYPO3 universe, raising an amount of 32.000,- € for paid development within a 90 day campaign on the crowd funding platform Startnext.

Since the Gridelements campaign had been quite favorable and was presented as a role model at several TYPO3 events, other TYPO3 related projects followed, with some of them being successfully funded, like the TYPO3 Theme Packages or TYPO3 mask in 2014.

BTW: This site has been done with both, Gridelements and Themes.

While there are several advantages for the crowd as a funder of extension development, there are some drawbacks as well. The clearly defined goals, the money being held in trust, the shortened time frame compared to association budgets, they all make crowdfunding an interesting choice. Still some projects miserably failed to reach their funding goal.

So there must be some pitfalls too, which is why we should take a closer look at this topic in another article about the subject.

Service Level Agreements

It's a matter of trust, not a question of cost

Starting with the prolonged LTS phase of TYPO3 4.5 another option appeared on the radar, which was quite new for the TYPO3 project, but actually had been available in the open-source world for quite some time already. Now that the TYPO3 Company has been founded they started to continue the successful concept of so called Service Level Agreements - aka SLA.

One of the most successful examples for the combination of open-source software and the SLA concept is RedHat, founded in 1993 and a 2 billion dollar global player today, creating a huge part of its revenue with services built around open-source.

Of course this is nothing that the TYPO3 project could currently be compared to, but still it shows, that in the business world people are willing to invest a lot more money as soon as they get a product they can trust.

So creating such a trusted environment for TYPO3 extensions in close collaboration with the TYPO3 Company and the TYPO3 core team could be another option for extension developers to still make a living based on a product they already shared for free.

The benefit of that collaboration is already visible each year at the TYPO3 User eXperience Week and the TYPO3 Developer Days, but since this would open up a completely new way of dealing with the financial aspects of TYPO3 extension development, we will investigate that topic in another article about the subject.

TL;DR - Conclusion

There are several financing options for TYPO3 extension developers, but which one fits best?

For TYPO3 extension developers there is a catch-22 situation to be solved, since it is hard to generate an acceptable income based on open-source software that has already been shared for free.

With donations, association budgets, crowdfunding and service level agreements we have got several ways of financing available.

We need to find out, which of them is most suitable for extension developers, so they can make a living based on their creations, while providing trustable solutions for TYPO3 agencies, integrators and users.

We would like to hear or read your opinions about the options we presented. Based on your feedback we will publish some more articles about the different variants, so in the end we all will have a better overview about the pros and cons of each option.

© Copyright 2026 Cybercraft GmbH

Coders.Care is the logical progression of the cooperation between providers of TYPO3 extensions and their users. Especially the point of communication during the preparation of a project will be optimized thereby. The developers can focus on their strenghts, while Coders.Care deals with questions, answers and management. In the consequence there will be clear statements about maintenance and further development of TYPO3 extensions, so the trust in TYPO3 and the projects implemented with it will be strengthened. As a TYPO3 agency we can only benefit of such a service.

Coders.Care is the logical progression of the cooperation between providers of TYPO3 extensions and their users. Especially the point of communication during the preparation of a project will be optimized thereby. The developers can focus on their strenghts, while Coders.Care deals with questions, answers and management. In the consequence there will be clear statements about maintenance and further development of TYPO3 extensions, so the trust in TYPO3 and the projects implemented with it will be strengthened. As a TYPO3 agency we can only benefit of such a service.